When generating frontend assets, you don’t want to add these generated files to your repository but it’s not always possible or easy to generate them on the production server either. In this article I’ll describe how to solve this issue using Jenkins.

What do we want?

When doing frontend development you will often use a build tool like grunt, gulp, or the flavour of the month. If you are not familiar with these tools, I recommend you look into them and see how they can fit into your workflow. The basic idea is that running the build tool will create the files that you want to use on your site. This starts at minifying your assets but there is a lot more you can do with it.

You can store the generated files in your repository and if you’re the only one working on a project that might work just fine. When you are collaborating on a project however, this will quickly lead to constant merge conflicts and the resulting frustrations. And besides, you generally want to keep your repository clean from generated code.

One solution for this is to build everything on deployment. This is a fairly straightforward and workable solution. This will make your deployments take longer but when everything is automated (and it is, right?) that’s not a major issue. The below snippet is an example of how you can do this with Capistrano.

namespace :grunt do

desc 'Do npm install'

task :npm_install do

on roles(:all) do

execute "cd '#{release_path}'; npm install --silent"

end

end

desc 'Do bower install'

task :bower_install do

on roles(:all) do

execute "cd '#{release_path}'; bower install --config.interactive=false"

end

end

desc 'Do grunt build'

task :grunt_build do

on roles(:all) do

execute "cd '#{release_path}'; grunt build"

end

end

before 'deploy:updated', 'grunt:npm_install'

before 'deploy:updated', 'grunt:bower_install'

before 'deploy:updated', 'grunt:grunt_build'

end

Unfortunately, this solution has its own problems.

The first issue is one of server maintenance. If you only have one server to deal with and you have complete control over it that might not be a problem, but scaling once again kicks in here.

While tools like Puppet, Chef, or Ansible help a lot in ensuring your servers have a consistent setup it is still a lot of potential extra maintenance work. And if you build your site or web app for a client you might not have the level of control over the server that you would need for this anyway.

As the number of npm modules grows quickly, this will also start to impact disk space (and especially inodes) which have to be taken into account for your server configuration. I haven’t even mentioned yet that building on your production server means you can’t test the result before it goes live.

To summarise, we don’t want to store the generated files in the repository as that will cause conflicts and frustrations during the development. We also don’t want to run the whole process during deployment as this requires extra server maintenance, which we don’t always have control over, the need for bigger disks, and other potential issues.

How do we solve this?

Enter Jenkins.

Regardless of what you’re building, a Continuous Integration system is useful. As I’ve explained in a previous article, I generate and deploy this site using a similar tool. While an introduction to Jenkins falls outside of the purpose of this article, you should still be able to follow along without any knowledge of the system.

In a way similar to how I generate this site, we can have all this generation take place on the Jenkins server. After executing all the usual checks, Jenkins will run the commands for the frontend generation and if successful will commit the results of this and push it up to a special release branch.

Depending on your workflow there will be some small differences in how you approach this. I will demonstrate using a workflow you might see in an agency where you have a staging branch from which you deploy to the client preview version and a master branch for the production site. Both of these branches receive pull requests from various feature branches.

The release branches that Jenkins will push to have the imaginative names of release/staging and release/master. These branches only exist as the source for deployments, and other than Jenkins nobody should commit to them.

We need to do two things to make this work. First we add extra functionality to the project’s build.xml file and then we’ll make changes to the project configuration in the Jenkins interface.

build.xml

We start by declaring a target named grunt that depends on all the other commands. This grunt target is then added to the main build target. The only purpose of this target is to make it more organised.

<target name="grunt" depends="npm_install,bower_install,grunt_build,add_dist,commit_dist" />

Next we define the commands that install the dependencies and the actual grunt build command. Here this consists of installing both npm and bower dependencies before we run grunt. We don’t want the build to succeed if there is a failure in this process, which is why the failonerror flag is on the last step.

<target name="npm_install" description="Install NPM dependencies">

<exec executable="npm">

<arg value="install"/>

</exec>

</target>

<target name="bower_install" description="Install Bower dependencies">

<exec executable="bower">

<arg value="install"/>

</exec>

</target>

<target name="grunt_build" description="Grunt build">

<exec executable="grunt" failonerror="true">

<arg value="build"/>

</exec>

</target>

And lastly we will add these generated files, using the -f flag because this directory should be in your .gitignore, and finally commit these changes.

<target name="add_dist" description="Add generated files">

<exec executable="git">

<arg value="add"/>

<arg value="-f"/>

<arg value="web/dist"/>

</exec>

</target>

<target name="commit_dist" description="Commit generated files">

<exec executable="git">

<arg value="commit"/>

<arg value="-m"/>

<arg value="Add Grunt generated files"/>

</exec>

</target>

When Jenkins runs it will carry out all of these actions so that if everything succeeds the end result is a single commit containing all of the generated files. Don’t forget to configure Jenkin’s git credentials, especially as you will need these for pushing up your changes later as well. Create an account for it, and dress it up in a nice way to make it all more fun.

Jenkins project configuration

So far, Jenkins will create this commit for us, and now we need to push this back up to origin. As it happens, the Jenkins git plugin has a post-build tool for this called the Git Publisher. With the help of this article I set it up like this.

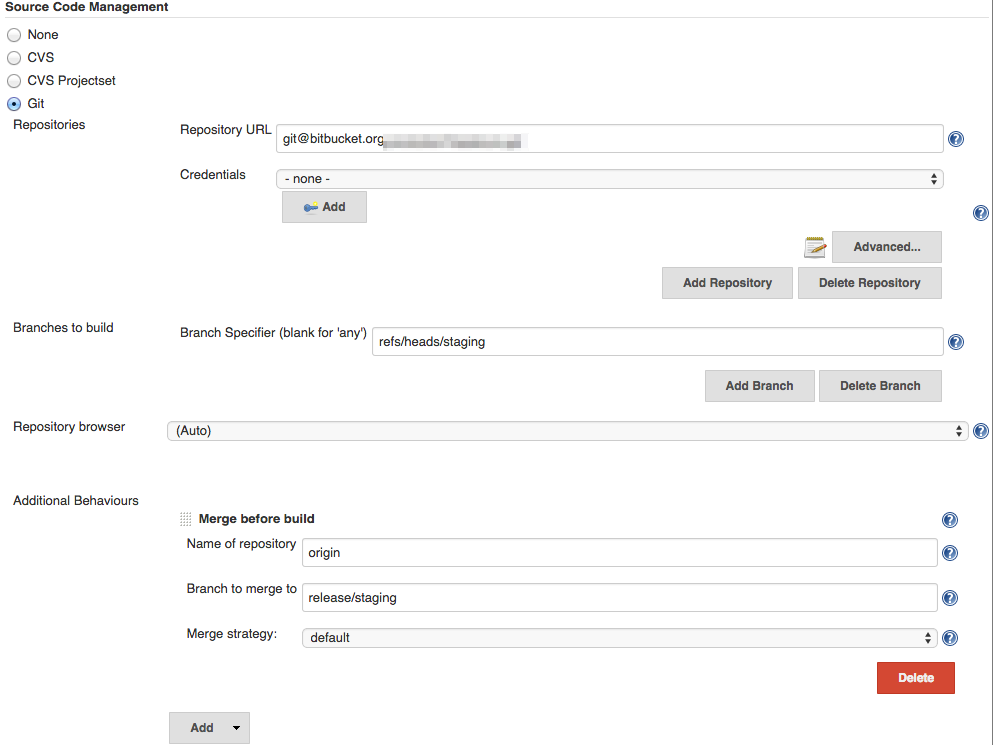

As you can see in the image, our configuration will create a tag as well as pushing it up to our release/staging branch. While you will need to push the result up to a branch, adding a tag as well is mostly a matter of taste.

Pulling in the staging branch and then pushing up these changes as well as the generated code will lead to conflicts because of previous sets of generated code that weren’t deployed. In order to prevent this we will therefore need to merge the release/staging branch into our checked out branch. We do this by adding the Merge before build additional behaviour in the Git configuration for the project.

To complete the setup, you then create a similar configuration for a Jenkins project that only checks the master branch, which will push its results up to the release/master branch.

The next step

Generating your production assets in your CI tool allows you to have both the benefits of keeping your working repository clean from your generated files, as well as easy control over the environment where this generation takes place.

This doesn’t have to be the last step in the build process either. You can add automated tests to check if all the generated assets are correct and present, or even hook it into your deployment tool for automated deployments.

A possible improvements to this process is to run it inside a Docker container. That way you don’t have to keep the Jenkins server configured but you can just provide a Dockerfile that will complete the build for you. And if your project doesn’t share server resources you can even skip pushing up the generated files, keeping your repository even cleaner, but instead use a tool like Packer to generate a server image where you can copy the generated assets to.

No doubt you can think of your own improvements as well, so don’t hesitate to let me know in the comments.

Read more like this:

- Using Docker for a more flexible Jenkins

- Week 14, 2018 - Jenkins X; Windows Server 2019; Azure Serial Console; Cloudflare Workers

- How to use Docker for a more flexible Jenkins

- Prepare deployable code using Docker and Jenkins

- GitHub Actions - Awesome Automation

Or always get the latest by subscribing through RSS, Twitter, or email!