In October I gave a Serverless Containers Deep Dive talk at the AWS Community Day and AWS User Group Conference, which focused on AWS Fargate. Below is a written version of these presentations, as well as the recording of when I repeated this talk at the Melbourne AWS User Group1. The slides by themselves are available on Speaker Deck.

What Are Serverless Containers?

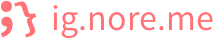

In order to talk about serverless containers, let’s take a quick step back and look at what containers really are.

Once upon a time we had to deal with hardware. Hardware can be annoying, it doesn’t scale well2 and it ends up giving you a lot of issues you might need to solve by going to a data centre somewhere. In addition it means that to have good utilisation you’ll end up running multiple applications together and all the headaches that might cause.

This was improved with the introduction of virtual machines. Instead of having to deal with the hardware directly, and a separate piece of hardware for anything that needed to be separate3, you can run many virtual machines on the same hardware. This means that you have both better utilisation as you can run multiple operating systems that are purpose fit, and it makes it easier to manage and scale.

But then we got containers. Made popular by Docker, containers offer a way to combine your application and all of its dependencies into a single package. These can then be run on different machines, virtual or otherwise, where these lightweight4 containers provide an additional layer of separation between the various applications. Containers will use parts of the underlying operating system such as the kernel, I/O, and networking, but these are all abstracted away by the runtime so the container doesn’t know what it’s running on.

But in the end this still leaves you with several layers that need to be maintained. After all, the container runs on top of your virtual machine, that you need to patch and update, and this in turn runs on top of the hardware that has the same requirements5. So how about we just get rid of that? Let’s remove that virtual machine, and the underlying hardware, and make it all serverless6. Or as I like to think of it: Serverless Containers IN SPACE!

As with all serverless technologies, this means that the containers run on (virtual) machines managed by someone else. However, as we don’t have insight into where these machines are I prefer to think of them floating high above us in space as that makes it more fun7.

How Do You Use Space Containers?

While there are multiple providers of serverless containers, I will focus only on the AWS solution for this: AWS Fargate.

Fargate was introduced at re:Invent 2017 and is a deployment method for ECS, the Elastic Container Service. Originally ECS only allowed you to deploy containers on instances you spin up and prepare yourself, but with Fargate you can now deploy it straight into “space”. Since its introduction there have been various improvements to Fargate, most of which are a result of improvements to ECS such as the just released support for resource tagging8, and most importantly it was rolled out to more regions.

How do we use ECS then to create a Fargate container? The below 5-minute video is one I recorded in January that shows me spinning up Fargate containers.

In essence though, it boils down to 2 steps:

- Create an ECS Task Definition

- Create a Task or Service using that Task Definition.

If you’re not familiar with the actual terminology used here you might want to use an analogy for the task, service, and task definition. If you compare it to EC2 Instances, you can think of the ECS Task Definition as an AMI9, a Task as the Instance, and a Service as an Autoscaling Group.

Both of these steps can be done through the Console, CLI, or something like CloudFormation.

aws ecs register-task-definition --family demo --container-definitions "[{\"name\":\"nginx\",\"image\":\"nginx\",\"cpu\":256,\"memory\":512,\"essential\":true}]" --network-mode awsvpc --requires-compatibilities FARGATE --execution-role-arn arn:aws:iam::123456:role/ecsTaskExecutionRole --cpu 256 --memory 512

aws ecs run-task --task-definition demo --network-configuration="{\"awsvpcConfiguration\":{\"subnets\":[\"subnet-123456\"],\"securityGroups\":[\"sg-123456\"],\"assignPublicIp\":\"ENABLED\"}}" --launch-type FARGATE

Looking at the above, you can see it’s fairly straightforward. A couple things to pay attention to are that you have to say a container is meant for Fargate both when you create the task definition and when you run the task. I’m not sure why, as it seems redundant, but it’s not a big deal either. Aside from that, you need to define the amount of memory and CPU your task requires when you create the task definition, and there is a limited number of allowed combinations here.

The other thing you need to pay attention to is the networking. In the task definition you have to specify that you wish to use the awsvpc networking mode, and then when you run the task you have to tell it which subnets and security groups to use while also deciding if the containers should get a public IP or not.

How Do Space Containers Work?

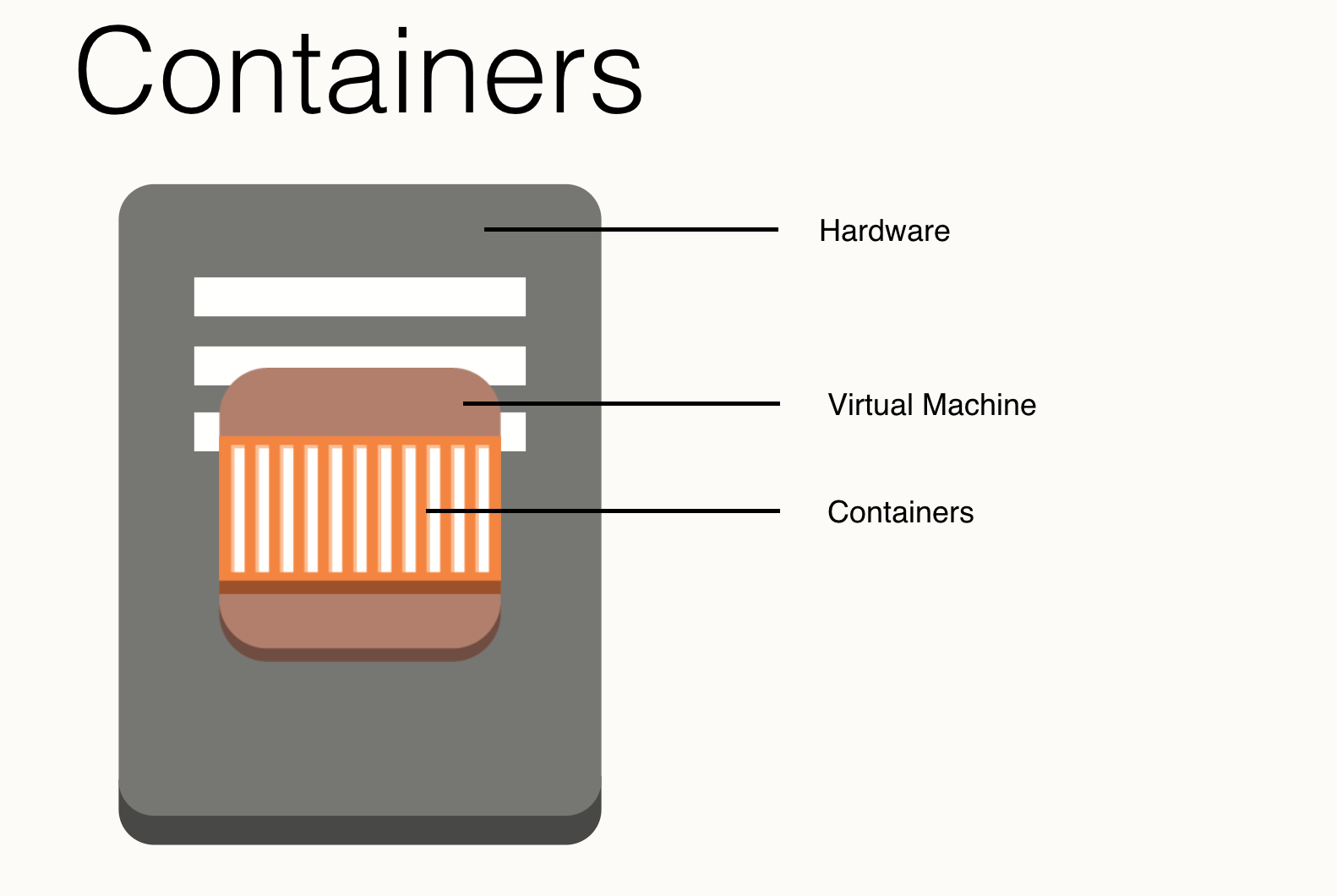

Now that we know how to spin up a Fargate container, let’s have a look at how this all actually works. After all, having a container up in space makes it a bit hard to use.

This is where the magic of the awsvpc networking mode comes in. When spinning up a container, it will create an ENI in the subnet you specified. An ENI is an Elastic Network Interface, which comes down to it being the thing that connects your compute power to the network. It is used for every type of compute that requires access to a VPC, and Fargate containers are therefore no exception.

Each container will have its own ENI, which means there are some limitations you need to keep in mind. First of, it means that if you spin up a lot of Fargate containers, you have a good chance to run out of private IPs in your subnets or run into service limits. In addition, a side effect of working this way is that your containers can only expose unique ports. In contrast, with EC2-based ECS you can have multiple containers in the same task listening to, for example, port 80, which can then be translated to different ephemeral ports on the instance.

As mentioned earlier, you can also give your tasks a public IP. In this case, you will be randomly assigned an Elastic IP to the ENI. It’s not possible to manage this EIP, so don’t expect a consistent public IP.

Of course, you can always attach the service to a load balancer to ensure it has a consistent endpoint. If your service is stateless and only needs to be available internally you can also consider using ECS service discovery which uses a multi value Route53 record and is therefore comparable to a round robin DNS.

Why Use Space Containers?

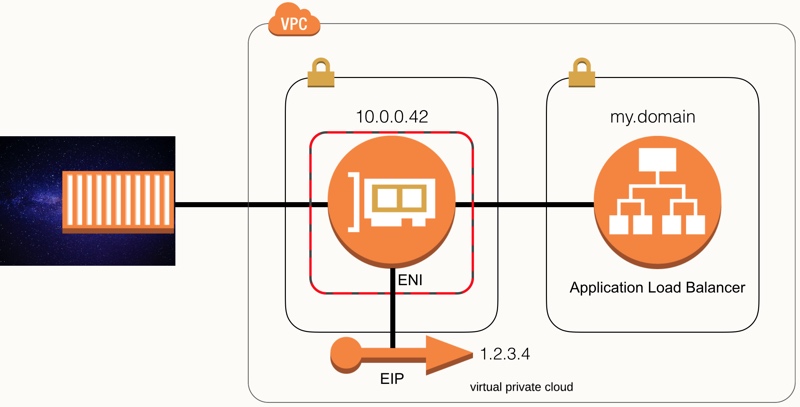

This is the biggest and probably most important question when considering a technology. Why would I use this? What are the benefits, and how do they weigh against the downsides? Especially when you consider the rest of the ecosystem that already contains several compute options such as EC2 instances, Lambda functions, and of course ECS on EC2.

In this case, let’s compare the different options using the below (non-scientific) diagram.

One the y-axis we have the average runtime of the compute option, while the x-axis shows how much time you spend on maintaining them10. Unsurprisingly, Lambda functions run for the shortest amount of time. Even with the recent increase to a 15-minute runtime, most of these functions will run for seconds at a time. Similarly, there is very little maintenance as AWS handles most of that for you, with the occasional reminder to please update your NodeJS runtime once the version you use is no longer supported.

On the other hand of the spectrum are EC2 instances. These will usually run for a very long time, ranging from days to years. And of course, these also require a lot of maintenance work even just to keep up with all the security patching. While you may (and should!) have automated this into your CI/CD pipeline, there is still work involved.

ECS on EC2 instances is similar, with the big difference that as you don’t care as much about the actual underlying host you will likely use the ECS-optimised images provided by AWS. In that case you probably only need to include a yum update in your user data and once in a while refresh the AMI11. You’ll still need to update your containers though, but that will usually happen as part of the application development.

Fargate on the other hand, doesn’t care about the underlying host at all, which makes it fall more on the Lambda side of the spectrum. You’ll still deal with the container side of things though, so there is more work than dealing with Lambda functions.

Based on this you can draw some conclusions where Fargate might be useful, but also remember that it’s very easy to draw diagrams like this and get any outcome you like. For example, if we focus on the price per second you’ll likely find that Fargate doesn’t come out nearly as positive.

In the end, what it comes down to is that you need to use the right tool for the job. So, let’s have a look at what potential jobs are where Fargate is the right tool.

1. Standard Workloads

Hopefully the section on how to run space containers has given you a feeling for how easy it is to run Fargate containers as services. You pay a bit more for using Fargate, but on the other hand you (or your team) can focus on more interesting matters than dealing with the underlying hosts.

In fact, once you’ve done it a couple of times you will find that it is quite boring. Don’t get me wrong though, when it comes to infrastructure boring is a good thing. It means that it’s predictable, stable, and won’t cause an alert at 3am in the morning.

2. On Demand

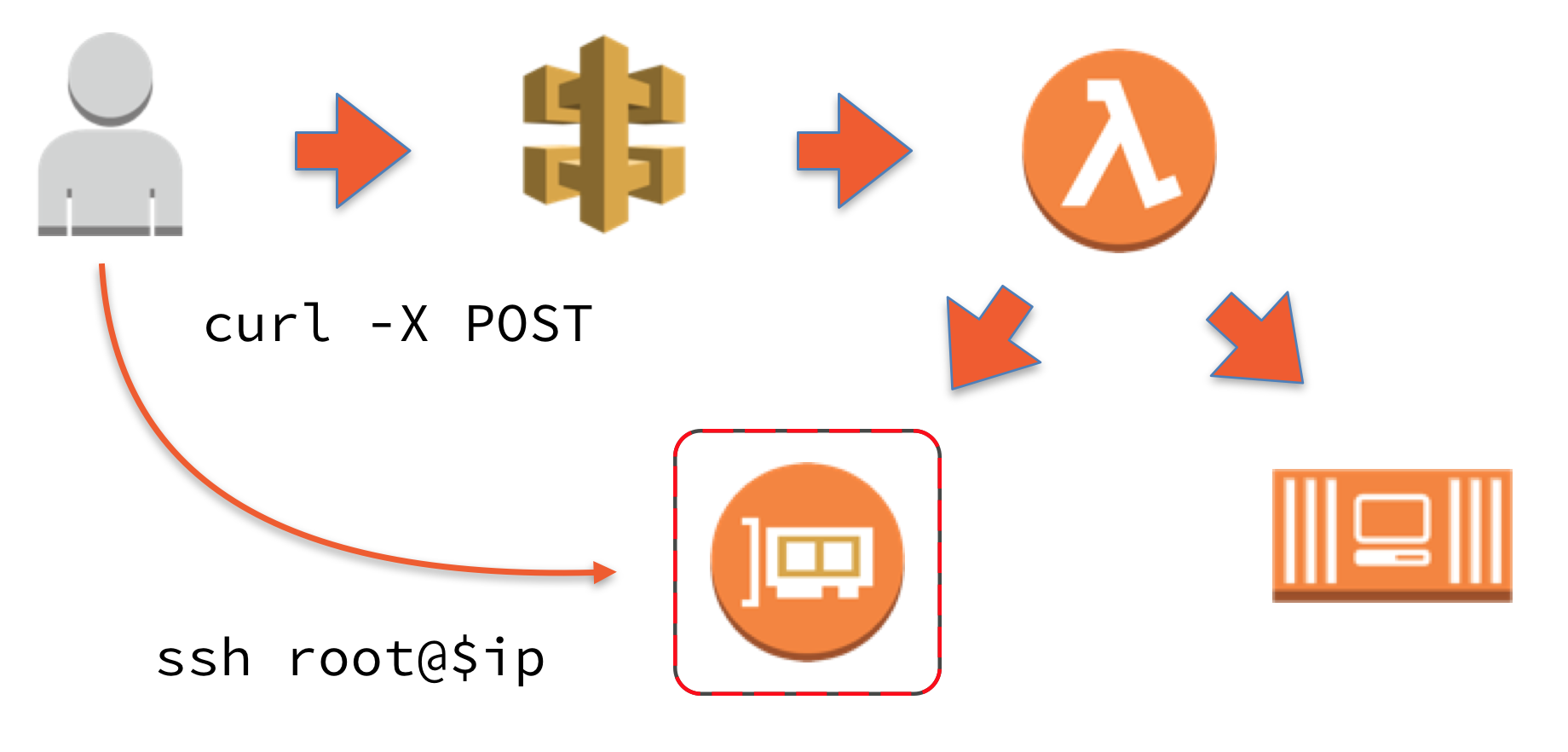

As with every AWS service, we’re not limited to just using the service by itself and we can build nice solutions. One example of this is the Serverless Bastion on Demand that I wrote and spoke about earlier in the year. This allows you to spin up a Fargate container into your environment that you can then SSH into to get access to instances you may have running in there.

With the introduction of the AWS Systems Manager Session Manager12, this particular use case has become less useful but the idea itself still stands. Using a Lambda function or something else, you can start a container when you need it and tear it down shortly after.

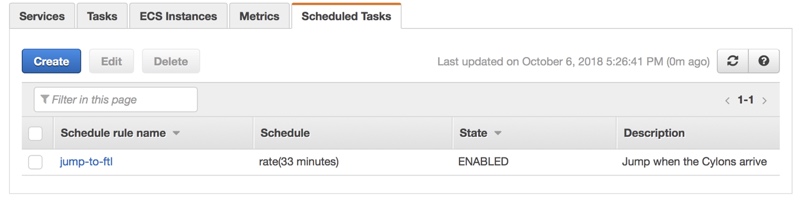

3. Scheduled Tasks

Of course, we can automate this as well. With the introduction of scheduled tasks for Fargate, it is possible to run jobs on a regular basis. One potential use case for this is to run cronjobs. While cronjobs have served the computing world well, they’re not quite as useful in a modern architecture where your application servers are autoscaling13. One workaround for this was to have a separate server that runs the cronjobs, but instead you can set up a task that does this. Aside from regular cron syntax, you can even set it up to run every x amount of time.

Limitations of Space Containers

As mentioned before, you need to have a look at the limitations as well if you want to see if something is useful to you. So let’s have a look at some of these14.

First, there is no support for IPv6. Even if you deploy it into an IPv6 enabled subnet, your Fargate ENI will not get an IPv6 IP. Speaking of IPs, I already mentioned that you have one IP per running task, and all the limitations that brings along.

Being a serverless technology you have less control over your runtime, so for example if you’re using Docker plugins this is not the solution for you. Similarly, keep in mind that you have to take into account that the local storage is not under your control so if you have persistent storage needs you will have to find a solution. There is support for volumes, but that doesn’t necessarily fulfil the needs you have for it.

The last limitation I want to mention is the lack of support for Windows containers. While I’m not a big fan of these, this obviously means that if you use Windows containers you can’t run these.

That said, the downsides of serverless technologies are countered by the upsides of it: you have less maintenance, don’t need to think about security as much, and you have a pay as you go model. And when you compare Fargate to Lambda you have the full capabilities of containers in your toolset. There is no need to limit yourself to what Lambda allows, or to switch to one of the blessed languages, you can run anything you want in your container15 and for however long you want to.

Go Build (in space)

To summarise this all, Fargate is a powerful tool that you can use. Between standard workloads, on demand tasks, and scheduled tasks I’ve given several use cases that might work, but in the end I don’t know your environment and what may or may not work.

Hopefully your take away from all this that Fargate allows you to do some things in a different way than you did before and that it gave you some ideas of how to use it. So, as our friends at AWS like to say: Go Build!

But do it in space.

-

The user group has recently started recording all presentations, check out their channel! ↩︎

-

Scaling down was easy, but scaling up could literally takes weeks. ↩︎

-

For example, Windows and Linux workloads. ↩︎

-

Containers can be as small as the application you run in it. ↩︎

-

Usually taken care of by your hosting provider/cloud environment. ↩︎

-

Which can be defined as: making everything below the application somebody else’s problem ↩︎

-

Yes, I probably read and watch too much science fiction. ↩︎

-

Although some ECS features aren’t available immediately to Fargate, like the new secrets. ↩︎

-

Or perhaps a Launch Template. ↩︎

-

Not taking into account any time spent on the application itself. ↩︎

-

Did you know you can automatically get the latest image from the Parameter Store? ↩︎

-

I still believe that name is silly. ↩︎

-

Which potentially means your job runs more than you want it, or gets cancelled due to a scaling action. ↩︎

-

Just in case of big announcements, this is posted before re:Invent 2018. ↩︎

-

Except Windows obviously. ↩︎

Read more like this:

- Serverless Bastions on Demand

- ig.nore.me For 5 Minutes: AWS Fargate

- Week 31, 2018 - Lambda SQS event source; ALB redirects; Application Auto Scaling; Fargate in Sydney

- Week 23, 2018 - Amazon Neptune; ALB Built-in Authentication; Helm in CNCF

- Week 19, 2018 - Operator Framework; gVisor; Stack Overflow for Teams; AWS CodeBuild Local Build

Or always get the latest by subscribing through RSS, Twitter, or email!