CloudFormation Macros were introduced recently, and they add a lot of power. In this article I want to take a look at how you can build and test one of these.

What are Macros?

Macros are a way to transform your CloudFormation template. You can write Lambda functions that change the template you’ve written (or a part of it) in order to get your desired result. This is the exact same functionality that is present in SAM templates, but with the difference that you are in control of the transformation that happens.

There are two different ways to use a macro, at the template level and snippet level. Template level transformations can change anything in the template, including adding and deleting resources, while snippet transformations are limited to just the snippet they are invoked in and its siblings. For these snippets your macro will still get the entire Resource provided, but you’re limited in your changes to that single Resource. These two have a different syntax for getting invoked.

Template level transforms are defined in the Transform section of your template.

# Template level transform

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: "2010-09-09"

Description: The dev environment VPC and subnets

Resources:

VPC:

Type: AWS::EC2::VPC

Properties:

CidrBlock: 10.42.0.0/16

Transform:

- NamingStandard

While resource level ones use the Fn::Transform function.

# Resource level transform

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: 2010-09-09

Resources:

MyBucket:

Type: 'AWS::S3::Bucket'

Properties:

BucketName: MyBucket

Tags: [{"key":"value"}]

'Fn::Transform':

- Name: PolicyAdder

CorsConfiguration:[]

All macros in the template are managed in order. The more specific a macro, the earlier it is handled. If the above transforms are used in a single template, the PolicyAdder will be handled before NamingStandard. Aside from this they are handled in the order of the template. If you have 2 template level macros they are parsed in the order you put them in.

Building a Macro

Let’s build our own Macro then, but let’s keep it simple1. Now, one of the advantages of CloudFormation is that you can reuse templates. However, one of the things that annoys me personally is that when you reuse templates the description is always the same2. As this has to be a string, we can’t fill it with our parameters to distinguish between our dev and prod environments or between different instances.

Let’s fix this with our new macro! The desired result is that if we deploy the following template with “DEV” as the value for the Identifier parameter:

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: "2010-09-09"

Description: The %s environment VPC and subnets

Parameters:

Identifier:

Type: String

Description: The unique identifier of the template

Resources:

VPC:

Type: AWS::EC2::VPC

Properties:

CidrBlock: 10.42.0.0/16

Transform:

- DescriptionFixer

That it will generate the following actual template3:

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: "2010-09-09"

Description: The DEV environment VPC and subnets

Parameters:

Identifier:

Type: String

Description: The unique identifier of the template

Resources:

VPC:

Type: AWS::EC2::VPC

Properties:

CidrBlock: 10.42.0.0/16

The Lambda Function

Usually I prefer to write my Lambda functions in Go, but in order to make it easier to deploy this one I’ll use a language we can inline into a CloudFormation template: Python.

As any Lambda function, our macro requires a handler function that serves as the endpoint and is responsible for returning the result. The event that gets passed to this contains all the parts that we need to fix the description of our templates. In this case we only need the fragment, which contains the template already parsed for use, and template parameters. The other information stored in event can be found in the documentation.

def handler(event, context):

# Globals

fragment = event['fragment']

templateParameterValues = event['templateParameterValues']

From the template parameters we then collect the Identifier and check if it contains a %s. This is only needed for error checking, because obviously we shouldn’t be adding the transform when this isn’t the case. If a %s is found, we override the value of fragment['Description'] with one where we replace %s with the identifier.

identifier = templateParameterValues['Identifier'].upper()

if '%s' in fragment['Description']:

fragment['Description'] = fragment['Description'] % identifier

Then finally we respond by returning the required values.

macro_response = {

"requestId": event["requestId"],

"status": "success"

"fragment": fragment

}

return macro_response

So, the next step would be to deploy this. But let’s assume we’re actually doing this the right way and build a test for this first.

Testing our Function

With the function written in Python, that makes the built-in unittest framework the obvious choice4.

import unittest

import macro

class TestStringMethods(unittest.TestCase):

identifier = "TEST"

event = {}

def setUp(self):

self.event = {"requestId": "testRequest",

"templateParameterValues": {"Identifier": self.identifier},

"region": "ap-southeast-2"}

def test_replacement(self):

self.event["fragment"] = {"Description": "%s template"}

result = macro.handler(self.event, None)

fragment = result["fragment"]

self.assertEqual(fragment['Description'], "TEST template")

def test_no_replacement(self):

self.event["fragment"] = {"Description": "static template"}

result = macro.handler(self.event, None)

fragment = result["fragment"]

self.assertEqual(fragment['Description'], "static template")

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

The unit test is pretty self-explanatory. I import both the unittest module and the macro itself (which is stored in the file macro.py) to ensure I can call the handler function. I define the main part of the event in the setUp function and then in the actual test functions I can just supply the template fragment directly as a Python object5.

Running the tests gives me the expected result and now we know our function is working correctly! Hurray!

The CloudFormation Template

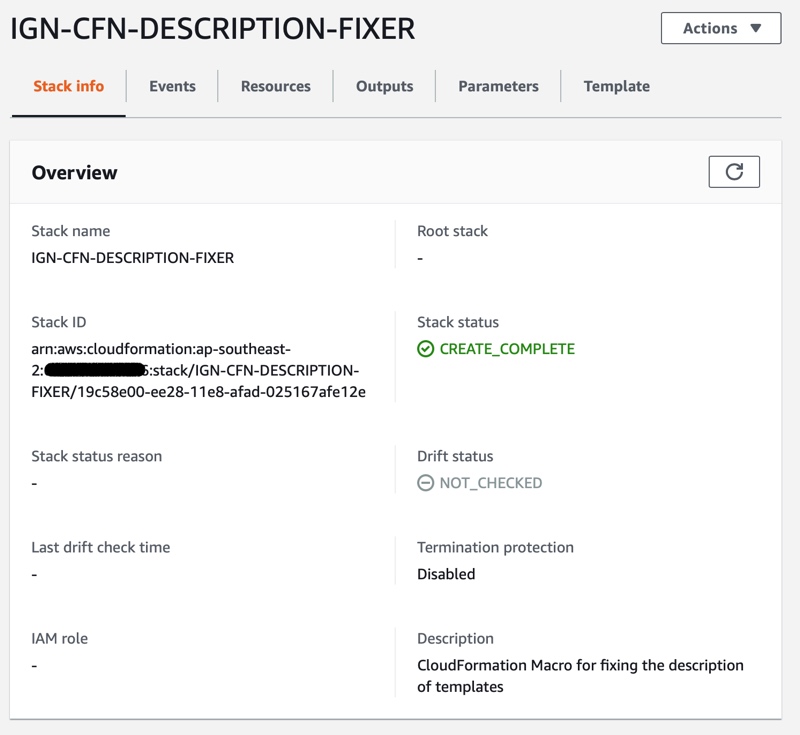

Now all we need to do is create a CloudFormation template for the macro and deploy it to my account. This part is easy actually, and is not much different from any other Lambda function. First, we define the execution role. This needs to be able to write the logs

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: 2010-09-09

Description: "CloudFormation Macro for fixing the description of templates"

Resources:

TransformExecutionRole:

Type: AWS::IAM::Role

Properties:

AssumeRolePolicyDocument:

Version: 2012-10-17

Statement:

- Effect: Allow

Principal:

Service: [lambda.amazonaws.com]

Action: ['sts:AssumeRole']

Path: /

Policies:

- PolicyName: root

PolicyDocument:

Version: 2012-10-17

Statement:

- Effect: Allow

Action: ['logs:*']

Resource: 'arn:aws:logs:*:*:*'

Then we need the function itself. As I mentioned earlier, to make it easier to distribute I’ve inlined the Python code. This means some copy/paste work, but is worth it6.

TransformFunction:

Type: AWS::Lambda::Function

Properties:

Code:

ZipFile: |

import traceback

def handler(event, context):

macro_response = {

"requestId": event["requestId"],

"status": "success"

}

# Globals

fragment = event['fragment']

result = fragment

templateParameterValues = event['templateParameterValues']

identifier = templateParameterValues['Identifier'].upper()

if '%s' in fragment['Description']:

result['Description'] = fragment['Description'] % identifier

macro_response['fragment'] = result

return macro_response

Handler: index.handler

Runtime: python3.6

Role: !GetAtt TransformExecutionRole.Arn

But it’s after this that we finally get to the interesting bits. First, we need to grant the function permission to be invoked from CloudFormation. And then we have to use the new AWS::CloudFormation::Macro Resource Type to set the name for our macro.

TransformFunctionPermissions:

Type: AWS::Lambda::Permission

Properties:

Action: 'lambda:InvokeFunction'

FunctionName: !GetAtt TransformFunction.Arn

Principal: 'cloudformation.amazonaws.com'

Transform:

Type: AWS::CloudFormation::Macro

Properties:

Name: 'DescriptionFixer'

Description: Fixes CloudFormation stack descriptions

FunctionName: !GetAtt TransformFunction.Arn

With the template written, we can deploy it. Obviously, we’ll use the command line for this.

aws cloudformation deploy --template-file DescriptionFixer/macro.yml --stack-name IGN-CFN-DESCRIPTION-FIXER --capabilities CAPABILITY_IAM

Let’s try it

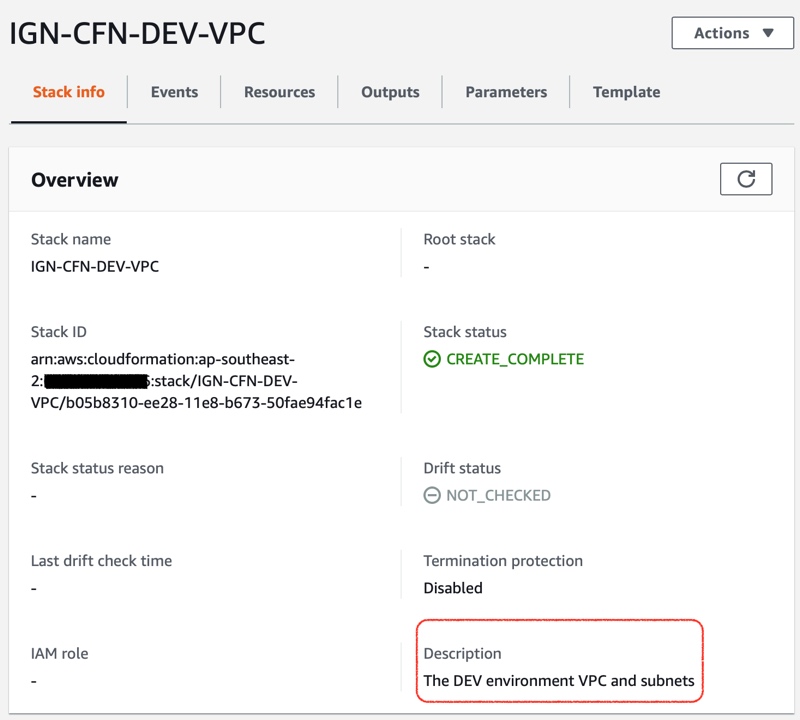

Now we can try out the sample template from earlier and see the transformation in action7.

aws cloudformation deploy --template-file DescriptionFixer/example.yml --stack-name IGN-CFN-DEV-VPC --capabilities CAPABILITY_IAM --parameter-overrides Identifier=DEV

And with that we’ve got our unique description. As usual, all the code used in this article can be found on GitHub.

As Complex as You Want It

While updating the description is a simple use case, you can do anything you want with the template, as long as it results in a valid CloudFormation template. Examples of other macros that I’ve written are a naming standard that enforces and applies a particular naming convention to all resources in a template8 and the expansion of short form Network ACL rules9.

The main takeaway though is that CloudFormation Macros allow you to do a lot more with CloudFormation and even allow you to customise how you want to write your templates. After all, there are many places where it seems extremely verbose and you just want to write a single line instead of 4 separate resources.

DSLs are Redundant

Let’s end this with a little side note. Four years ago10 I wrote about using CFNDSL to build CloudFormation templates. While DSLs have their own quirks, at the time using a tool like this was the best way to make your templates more flexible and it allowed you to do more complex things such as loops. Even conditionals, have existed for a long time in CloudFormation, but they don’t give the flexibility and power you can get with an actual programming language. And of course CFNDSL meant you didn’t have to use JSON directly, always a good thing.

Since that time however, there have been many improvements to CloudFormation. The two with the biggest impact are the support for YAML as a way to write the templates and the Macros I’ve just been talking about. Between these two I’m happy to make the case that tools like CFNDSL are no longer needed. Using YAML solves the mess that JSON can be11, and as we’ve seen the Macros give you the same power to make changes to your templates using a programming language.

This doesn’t mean that I think you should change your existing projects, but I would recommend against using a DSL for anything new and instead embrace the power of Macros.

-

Yes, you can do super complex things, but for demonstration purposes simple is best. ↩︎

-

Yes, it’s a minor thing and not something people usually pay attention to, but it’s there for a reason. ↩︎

-

Ok, under the hood it actually generates a JSON template, but for readability I’m displaying it as YAML. ↩︎

-

I’m not familiar enough with Python to know if there’s a better testing framework. If there is, I’m happy to hear about it. ↩︎

-

Remember, it automatically gets translated into this before reaching the Lambda function. ↩︎

-

Of course, you can automate this by using a main template with a placeholder in the ZipFile property that you then replace with the contents of the Python file. ↩︎

-

Don’t use deploy for anything but testing, make sure you can verify the Changeset before rolling it out. ↩︎

-

Using Name tags and resource specific name fields. ↩︎

-

Based on the great work by Kablamo in this VPC builder (updated on 2018-11-25 with link to newer version). ↩︎

-

I really need to do a new version of that post. ↩︎

-

Yes, I know some people believe JSON is human readable. They are wrong. Unless you compare it to XML of course, then JSON wins. ↩︎