Recently I had the opportunity to add a major1 feature to the Azure builder in Packer. This article is a written version of a presentation I gave about this at the Golang Melbourne meetup and is aimed at looking at the technical parts of that feature and how a builder actually works within Packer.

The problem

Before diving into the problem I’ll take a moment to explain what Packer is, just in case you’re not familiar with it. Packer is a tool to create virtual images for your virtual machines. Aside from being a good way to automate this creation, it also allows you to do this for multiple environments. That means that in theory you can use the same configuration to build a Docker image, an AWS AMI, a Virtualbox image, and many more.

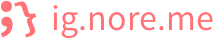

The problem I ran into and that prompted this feature was in the Azure builder. In Azure, resources are grouped together into Resource Groups2. This is useful for many things, but sometimes you wish to restrict access for a user or process to a particular resource group. However, the Azure builder in Packer would always create a new resource group and delete this afterwards as part of the cleanup. Technically speaking, it was possible to provide the name of an existing resource group, and while it then wouldn’t need to create a resource group it would still remove it afterwards. Which might result in a, let’s say, less than perfect situation as everything else in that resource group was also removed.

The solution

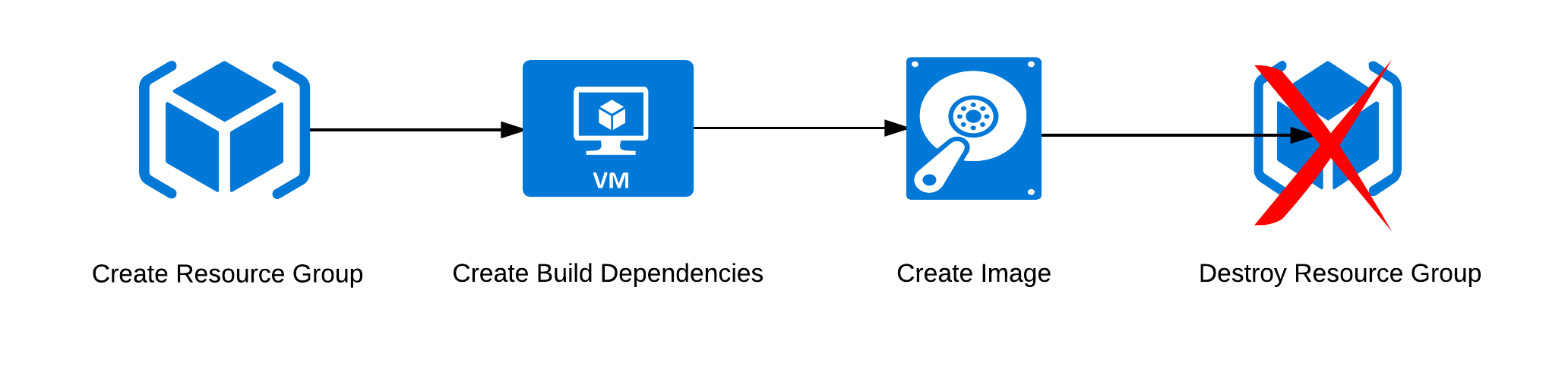

The cleanest way to solve this was to leave the existing path alone and instead add a second path. This second path will then skip the “Create Resource Group” step and immediately deploy the required infrastructure for the build into the existing resource group. Thus far this behaves similar to the existing path, and the biggest change is therefore in the cleanup. Instead of simply destroying the entire resource group, the code will go through everything that was created3 and delete it in reverse order.

My initial plan here was to make it automatically detect whether the requested resource group already exists, and then have the code decide how it should clean up. That was how I initially implemented it, but if you look at the discussion in the pull request I made this was not appreciated. The Packer maintainers prefer if decisions are made explicitly by the user. I can completely understand that, as it ensures consistent behaviour. Changing the behaviour for that wasn’t hard either, but it did mean I included some checks to ensure no more accidental deletions of resource groups happened.

Enough background though, let’s have a look at how things work!

Packer Builders

If you’re familiar with Packer, you will likely remember that it works in steps. So, when you define your template you configure your provisioners4 as individual steps.

"provisioners": [

{

"type" : "file",

"source" : "test.txt",

"destination" : "/tmp/test.txt"

},

{

"type": "shell",

"inline": ["apt-get install nginx"]

}

]

The builders are configured in a similar manner. Each part of the process is defined in an individual step. We can see that here, in the builder.go file from the Azure ARM builder.

if b.config.OSType == constants.Target_Linux {

steps = []multistep.Step{

NewStepCreateResourceGroup(azureClient, ui),

NewStepValidateTemplate(azureClient, ui, b.config, GetVirtualMachineDeployment),

NewStepDeployTemplate(azureClient, ui, b.config, deploymentName, GetVirtualMachineDeployment),

NewStepGetIPAddress(azureClient, ui, endpointConnectType),

&communicator.StepConnectSSH{

Config: &b.config.Comm,

Host: lin.SSHHost,

SSHConfig: lin.SSHConfig(b.config.UserName),

},

&packerCommon.StepProvision{},

NewStepGetOSDisk(azureClient, ui),

NewStepPowerOffCompute(azureClient, ui),

NewStepCaptureImage(azureClient, ui),

NewStepDeleteResourceGroup(azureClient, ui),

NewStepDeleteOSDisk(azureClient, ui),

}

}

Each individual step has a clear and defined purpose. In fact, each step will implement the Step interface from the mitchellh/multistep library. This means that it has 2 functions, Run is meant to run the task and Cleanup will do the cleaning up afterwards5. The task runner will therefore go through each step in both directions.

As you can see by the names of the steps in the Azure ARM builder, most of the cleanup here is actually done by the delete steps at the end instead of using the CleanUp function. The reason for this is simple, when most of the cleanup consists of removing the resource group this is a straightforward way of ensuring that. To be clear, when a provisioning run fails it will stop where this happens and then run backwards through the remaining step. For this reason, the StepCreateResourceGroup also contains Cleanup code that removes the Resource Group, but which is only executed when StepDeleteResourceGroup was not executed.

So, this is the environment where I had to ensure the feature worked as intended.

StepCreateResourceGroup

I’ll walk through a number of the things I’ve touched, hopefully giving you an idea of how this works and what I did. If you want to see all changes I’d recommend looking at the pull request though.

The first change had to take place in the StepCreateResourceGroup step. Please keep in mind that for readability I’ve removed all if the if err != nil statements6 in the various code snippets as well as some other parts.

func (s *StepCreateResourceGroup) Run(state multistep.StateBag) multistep.StepAction {

// Validation, most output, and error handling removed for readability

var resourceGroupName = state.Get(constants.ArmResourceGroupName).(string)

var location = state.Get(constants.ArmLocation).(string)

var tags = state.Get(constants.ArmTags).(*map[string]*string)

exists, err := s.exists(resourceGroupName)

// If the resource group exists, we may not have permissions to update it so we don't.

if !exists {

s.say("Creating resource group ...")

err = s.create(resourceGroupName, location, tags)

if err == nil {

state.Put(constants.ArmIsResourceGroupCreated, true)

}

} else {

s.say("Using existing resource group ...")

state.Put(constants.ArmIsResourceGroupCreated, true)

}

return processStepResult(err, s.error, state)

}

While the if statement is obvious, the more interesting part is likely the call to s.exists. This is because while these steps have their own private functions, these are actually injected into the object on instantiation. My lack of professional work in Go may mean that this is a very common design pattern, but I haven’t run into it before. That said, I like it for how it makes it easy with testing, as your tests can easily use stubs instead of the full functions.

func NewStepCreateResourceGroup(client *AzureClient, ui packer.Ui) *StepCreateResourceGroup {

var step = &StepCreateResourceGroup{

client: client,

say: func(message string) { ui.Say(message) },

error: func(e error) { ui.Error(e.Error()) },

}

step.create = step.createResourceGroup

step.exists = step.doesResourceGroupExist

return step

}

Here we see that the code called by step.exists is actually the function doesResourceGroupExist.

func (s *StepCreateResourceGroup) doesResourceGroupExist(resourceGroupName string) (bool, error) {

exists, err := s.client.GroupsClient.CheckExistence(resourceGroupName)

return exists.Response.StatusCode != 404, err

}

CheckExistence is part of the Azure Go SDK, so we can safely assume that’s not something we need to dive into any further. That said, I would have preferred a cleaner method than checking the status code of the response.

StepDeployTemplate

Where StepCreateResourceGroup only required a change in the Run section, the biggest changes for StepDeployTemplate are in Cleanup. After all, while we skip the creation of the resource group after that there isn’t really any difference until we reach the teardown. And the first place we reach this teardown is right here.

A small aside, resources in Azure7 are created by way of templates that are then deployed. Even if you deploy things through clicking in the Azure Portal8 in the backend it will create a template and deploy this. This template then contains a number of operations, which correspond to the actions taken and resources impacted. In this case, that will always be the resources that were created.

func (s *StepDeployTemplate) Cleanup(state multistep.StateBag) {

//Only clean up if this was an existing resource group and the resource group

//is marked as created

var existingResourceGroup = state.Get(constants.ArmIsExistingResourceGroup).(bool)

var resourceGroupCreated = state.Get(constants.ArmIsResourceGroupCreated).(bool)

if !existingResourceGroup || !resourceGroupCreated {

return

}

ui := state.Get("ui").(packer.Ui)

ui.Say("\nThe resource group was not created by Packer, deleting individual resources ...")

Originally this function was empty, so the first part of the Cleanup is dedicated to ensuring that we simply pass by if this is following the original path.

var resourceGroupName = state.Get(constants.ArmResourceGroupName).(string)

var computeName = state.Get(constants.ArmComputeName).(string)

var deploymentName = s.name

imageType, imageName, err := s.disk(resourceGroupName, computeName)

This is then followed by collecting the required details, after which we can then actually start doing some work. In the code below you immediately see something terrible, a magic number. This is because I couldn’t find a way to get the number of operations in a deployment, and you can’t just ask for all of them.

if deploymentName != "" {

maxResources := int32(50)

deploymentOperations, err := s.client.DeploymentOperationsClient.List(resourceGroupName, deploymentName, &maxResources)

for _, deploymentOperation := range *deploymentOperations.Value {

// Sometimes an empty operation is added to the list by Azure

if deploymentOperation.Properties.TargetResource == nil {

continue

}

err = s.delete(*deploymentOperation.Properties.TargetResource.ResourceType,

*deploymentOperation.Properties.TargetResource.ResourceName,

resourceGroupName)

}

// The disk is not defined as an operation in the template so has to be

// deleted separately

ui.Say(fmt.Sprintf(" -> %s : '%s'", imageType, imageName))

err = s.deleteDisk(imageType, imageName, resourceGroupName)

}

}

The resources are returned in reverse chronological order so that the latest one created comes back first. This means we can simply walk through them and delete them one by one, knowing that there are no dependency issues. Unfortunately, not everything is added as an operation so the disk used by the build virtual machine needs to be deleted separately afterwards.

func (s *StepDeployTemplate) deleteOperationResource(resourceType string, resourceName string, resourceGroupName string) error {

var networkDeleteFunction func(string, string, <-chan struct{}) (<-chan autorest.Response, <-chan error)

switch resourceType {

case "Microsoft.Compute/virtualMachines":

_, errChan := s.client.VirtualMachinesClient.Delete(resourceGroupName,

resourceName, nil)

case "Microsoft.KeyVault/vaults":

_, err := s.client.VaultClientDelete.Delete(resourceGroupName, resourceName)

return err

case "Microsoft.Network/networkInterfaces":

networkDeleteFunction = s.client.InterfacesClient.Delete

case "Microsoft.Network/virtualNetworks":

networkDeleteFunction = s.client.VirtualNetworksClient.Delete

case "Microsoft.Network/publicIPAddresses":

networkDeleteFunction = s.client.PublicIPAddressesClient.Delete

}

if networkDeleteFunction != nil {

_, errChan := networkDeleteFunction(resourceGroupName, resourceName, nil)

}

return nil

}

The s.delete call from Cleanup points at the above function, which handles the actual deletion. Unsurprisingly, this mostly consists of calls to the various Azure clients. I am quite happy though with the networkDeleteFunction code which means that for those at least I didn’t need to deal with the same error handling over and over. That said, I’m not sure why some of the delete functions in the Azure client use different interfaces so I couldn’t do this same thing for all of them.

One other thing here, is the case for the KeyVault. Unfortunately I didn’t write that, as it’s something that is only used with Windows VMs and as I didn’t use those I never did a complete test with that9. This wasn’t actually discovered until people started using it and ran into this issue, at which time it was fixed by a code owner10.

Getting this into the project

While there is more code that could be looked at, it’s very similar to the above and most of the work involved was really just making sure that everything worked as intended. If you really want to look at all the code, I’ll refer you again to my original pull request as well as the codebase in general. There are plenty of things that I believe could be done better, and I’m sure that some of you will have ideas about doing so. To be clear, this translates to: I wouldn’t mind hearing about improvements I could have made or better ways to solve this.

That said, keep in mind that this was an open Issue in Packer for a long time and it was therefore up to me to solve it. Which I did, and in a way that I’m reasonably happy with. The actual contribution is then the last thing I want to talk about. After all, an open source project ends up working the way its contributors want it to. If you don’t say anything, nothing happens, and feature requests that are not interesting to contributors will take a long time to be implemented11.

In that regard, Packer seems to be doing things right. There are clear directions on how to build the project, how to deal with dependencies, and how to go about creating your pull requests. A lot of this is standard to this kind of project, but I also got pretty quick responses to my PR and the conversation in there was all helpful. So, that part I’m happy about.

In addition, I now get tagged into some Issues that crop up in this part of the code. So far that’s meant fixing some small things here and there but I’ll be honest, it feels nice to be included in something like that.

-

In my opinion at least. ↩︎

-

An obvious name. ↩︎

-

Yes, it creates a lot more than just the Build VM ↩︎

-

The individual steps that are taken to provision your image. ↩︎

-

Again, very obvious names. ↩︎

-

So please don’t complain about them not being there. ↩︎

-

At least in the modern ARM environment. ↩︎

-

The interface of which still makes me feel like crying every time I have to use it. Yes, it is that bad. ↩︎

-

Oops? ↩︎

-

As in, the person responsible for the Azure part of the project. ↩︎

-

We all have things in projects that we’d like to see differently. But the best way to make something happen is to implement it, or possibly incentivise someone else to do so. ↩︎

Read more like this:

- aws-sdk-go-v2 is finally GA

- Go-ing Lambda

- Trying out the new AWS Go SDK

- Publishing Go binaries with Wercker

- Starting with Golang

Or always get the latest by subscribing through RSS, Twitter, or email!