Security is many things but easy is not one of them. This talk was given at the AWS User group meetup in Melbourne on the 27th of September, 2017. It focuses on showing you how to harden your environment using only tools that AWS provides and contains practical solutions ranging from basic to advanced. You can either watch the recording or read below for a textual version.

Security

Before we move on to the more practical side of things, let’s have a quick definition on what security is, why it’s important, and how AWS can help you with this.

For today we’ll take a very high level definition of security:

Security is the means to prevent bad things from happening.

What exactly “bad things” are can differ per use case, but in an online service situation examples include ensuring your website stays up and not be featured in the news for having private information from your customers get stolen. To be clear, the issue in this example is that the information was stolen, not that this then becomes a news item.

We’ve all seen recent and not so recent cases where data breaches have been made public and no doubt there have been even more where we didn’t hear about it yet. The big takeaway from these events is that if you put something on the internet you will become a target, and if you’re an interesting enough target you will likely get breached. One step in dealing with security is therefore to assume that this is going to happen so that you can start building an appropriate defensive strategy.

To do so, we start by asking ourselves questions. Questions such as what is the most important thing to protect and who should have access to what? But also, questions about the trade offs you may need to make concerning usability. As you come up with these questions you might not have answers for all of them, but that’s alright as security is a moving target. We learn from the past, both our mistakes and those of others. This means both that you will add new protection measures, but also that sometimes new tools become available that mean you no longer need to maintain your old ones.

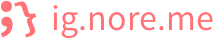

In an AWS context, this last part is extra important. It’s uqnlikely that your company has as many security specialists and time to build tools for it as AWS. There may always be things that your team can handle better, but obviously it’s better if they focus on that instead of redoing work that can be built on. This idea is codified by AWS as the Shared Responsibility Model.

The Shared Responsibility Model holds that AWS takes care of all security requirements up to a certain level, and that you will need to handle everything that isn’t covered by this. For example, this means that you don’t need to worry about the security of the hardware your applications run on, but you are responsible for ensuring the operating system on your EC2 instances is fully updated and secured. The level that AWS' responsibilities go differs per service, with managed services like RDS requiring less work from your side than the more basic EC2 service.

On top of the Shared Responsibility Model, AWS offers a number of tools and services that can help you secure your environment. One of these is the Well-Architected Framework whitepaper. This whitepaper details the questions AWS believes you should ask yourself when designing an infrastructure, and contains a section on security with a number of questions aimed to make you consider things such as how you are protecting access to your root account and managing logs.

Another tool you should keep an eye on is the Trusted Advisor. This is accessible through the Console and not only shows you things such as how to get potential cost savings, but also has a section concerned with security. It doesn’t go very deep, but it will highlight a lot of the common security problems that you can often fix with minimal effort.

Monitoring and alerting

This then brings us to the first major topic to discuss: monitoring and alerting. Monitoring is too often handled last when setting up security, but the case can be made that there is no real security if you’re not monitoring it. If you don’t know whether you’ve been breached, you don’t know if anything was stolen. If you don’t monitor what has changed about your environment you may not notice if something was opened that you didn’t mean to.

AWS has a number of tools that can be used for monitoring and frequently updates and improves them. All of these can be set up to trigger alerts when things happen that are out of the norm using regular CloudWatch Alarms.

The first thing you’ll want to ensure is set up is CloudTrail. CloudTrail logs all of the AWS API calls that are made in your AWS account. This includes simple actions like logging into the Console, but also starting or stopping specific services. The first purpose of this is therefore to act as a log where you can trace back who committed a certain action.

There are a couple of things you can do to improve on the basic functionality of CloudTrail as well. The first step is to push the logs to a different account. The advantage of this is that this lowers the risk of someone who gained access to your account changing or deleting the logs that are stored on S3 as they are in a different account. Secondly, you can configure CloudTrail to push its data to CloudWatch Logs. This in turn means you can set up Metric Filters that can trigger CloudWatch Alarms when certain actions happen. When you enable this integration through the Console, AWS even offers to create a number of Alarms for you.

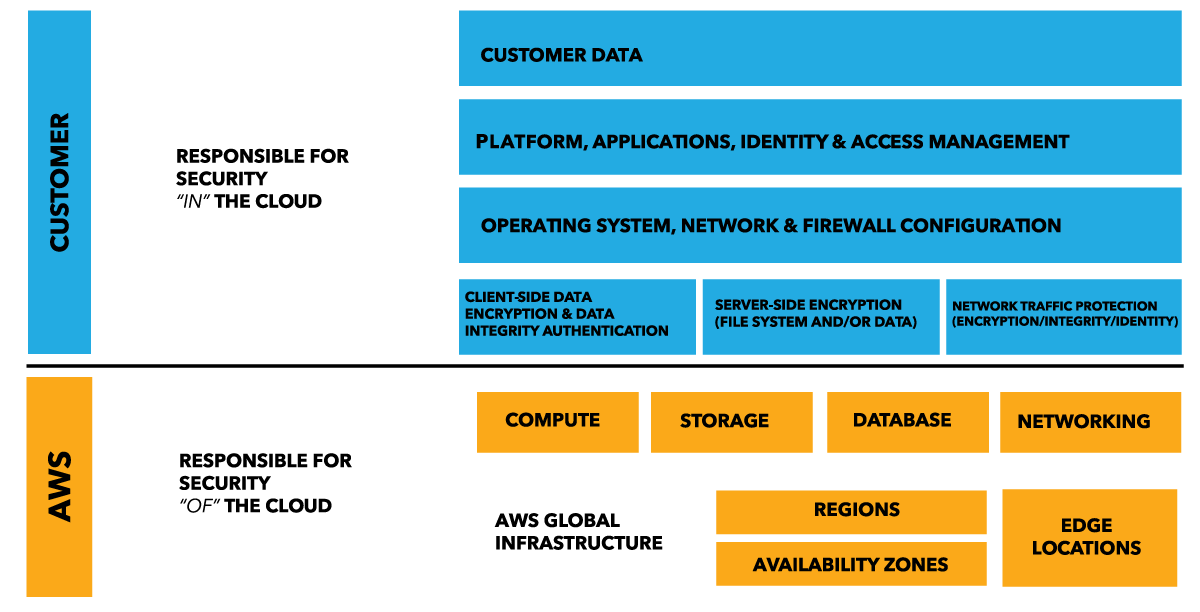

If you want the ability to monitor specific settings of your environment you can do so with AWS Config. Where CloudTrail records all API calls, the main purpose of AWS Config is to record configuration changes that have been made to your resources. And as with CloudTrail, the results of this can be logged to an S3 bucket in a different account. An example of such a change would be if you open up port in a security group.

This is great for auditing, but it actually goes a step further as well. You have the option to configure AWS Config to monitor your resources in a way that it compares it to your desired configuration and if it discovers that this is no longer the case it will trigger an alarm. In the above example of opening up a port, you can have a rule to monitor this and it will then show up in the Config Dashboard.

In addition all of these events can be sent to an SNS topic, although you will then need to process this yourself to distinguish between simple notifications and important changes. What this means is that if you use CloudFormation we can automate some of this compliance. Earlier this month, AWS introduced Rollback triggers in CloudFormation. This means that aside from just getting a regular alert you can now use CloudWatch Alarms to trigger the rollback of a deployment. For example, if you have AWS Config set up to ensure your environment doesn’t have port 22 opened up to the world you can use a Lambda function to check notifications for this and trigger an alarm which would in effect roll back the CloudFormation deployment that triggered this.

Aside from these, there is a lot more you can do with regards to monitoring. VPC Flow Logs will give you insight into the traffic in your VPC and similarly set alerts, and you can achieve a similar result at an application level by pushing the logs to CloudWatch Logs. Most services have their own way of monitoring things as well, and all of them can be connected to CloudWatch Alarms. Which actually lets us extend the claim made at the start of this section: without monitoring there is no security, and without alerts there is no monitoring.

With monitoring done, let’s have a look at setting up all this security then.

Account security

This section is brief only because AWS puts such a big emphasis on it every chance they get, so we don’t need to go over it in depth again. Ensuring that the access to your account is properly configured is very important from a security perspective so please ensure that you do so.

That means that you shouldn’t use your root account for day-to-day work, but instead do everything using IAM users. These users should be configured with Multi-Factor Authentication if they require access to the Console and you can configure the requirements for their passwords using a Password Policy to ensure it matches your company’s standards. Similarly any user’s API keys should be regularly rotated and you should try to do the same for any third-party applications that access your account through API keys.

When creating users you should also limit their access as much as possible. Creating groups and assigning your users to them makes this a lot easier to manage. Limiting access goes extra for any third-party accounts. While most services nowadays will ask only for what they need, there is always a risk that the access they want is more than they actually require. So, please review this access.

Another way of dealing with your account access is Federation. Federation allows you to use your internal authentication system, for example Active Directory, and hook that into your AWS account. Anyone logging in will then be assigned a role instead of a user and have temporary credentials. This means that they will automatically be logged out after a while, and that even if someone gains access to these credentials they will become invalid within a short while.

Infrastructure security

Let’s focus on infrastructure now, and your VPC related infrastructure in particular. A lot of security options here come built-in, but there is always a chance to get more out of this.

First a small digression though, away from the tools and more about focused on a method for dealing with your infrastructure: using immutable resources. If you’re not familiar with the term, in short this means that you don’t make changes to your instances once they’ve been deployed. Whether you do this by installing everything through user data or by baking your own AMIs doesn’t matter as much, it’s all about ensuring you don’t make changes to the servers afterwards.

If you have an auto scaling setup this is likely something you already use as otherwise you’ll lose your changes when a scaling event occurs. For single instances however you may not have set this up yet, but from a best practice perspective it is something you should aim for. Which then actually leads us to the first question to ask ourselves for this: Who needs to be able to log into these instances?

Generally the only people logging into your servers would be people who need access to the logs, those who need to do some patching, and anyone who needs to trigger a specific task. So, how do you control this access? For Linux instances you can use SSH-keys, but Windows is still password based. Although you require a key to get the admin password from the Console. Which then leads to the next question. How do you control access to these keys, and how do you handle rotation of them?

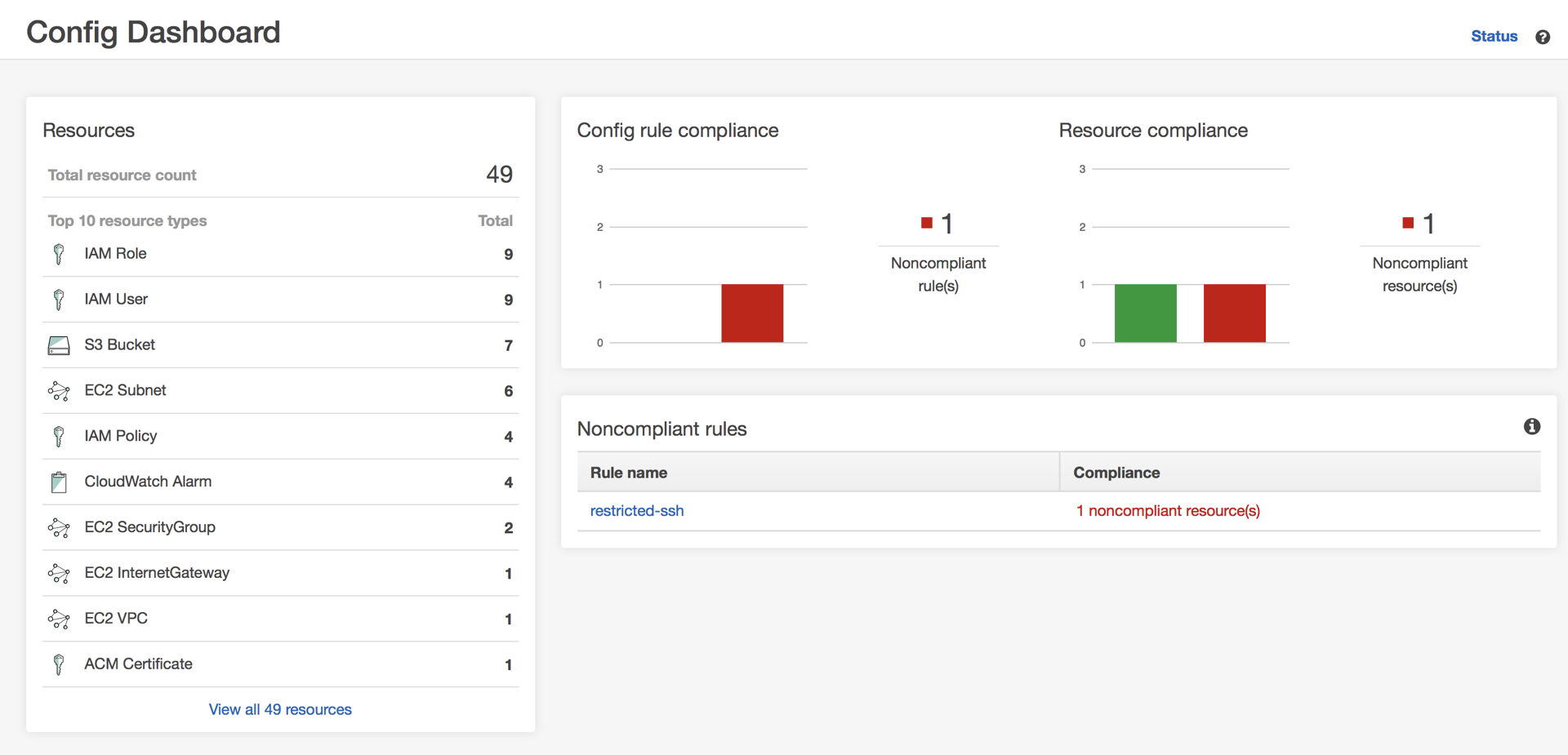

One way at least of managing the access is by storing the details in the Parameter Store.

This means you can specifically grant IAM Users or Roles access to this data and when you rotate keys or passwords you can simply update it in that one place. Unfortunately, those who use it will still need to download the keys to their local environment where it’s out of your control.

But maybe, instead of wondering how we control access to these things, we should be asking if we even need keys at all? Can we instead make the instances inaccessible even to ourselves? There was a good talk about this at last year’s RE:Invent, but basically it comes down to ensuring you don’t need access. As mentioned earlier, application but also system logs can be offloaded using CloudWatch Logs. If we have an immutable infrastructure you wouldn’t do any patching on the machines, and in case you do need to run something on the servers you can do so using the EC2 Systems Manager Run Command. Which not only ensures you don’t need to log in, it also means you’ve got an audit trail of who did what on each server.

Security Groups are something anyone who has built EC2 instances will be familiar with, and after restricting access on the instance this is the next layer in the defence of your infrastructure. Security Groups work as a shared firewall, allowing you to define access to the EC2 instances behind it. So, the question to ask ourselves here is who and what needs access?

We can limit access to specific IP ranges and security groups so whenever possible we should do so. There is no benefit in opening up ports that you’re not using. If you have a firewall, does it really need all the ports open to the world? That just opens an extra attack vector and makes your firewall have to work harder for no reason. Managing the various rules can be hard though, but about a month ago, AWS introduced a feature to help with this. It’s now possible to add a description to your rules. Which means that you can use this as part of your security setup by having the infrastructure explain why this access is there.

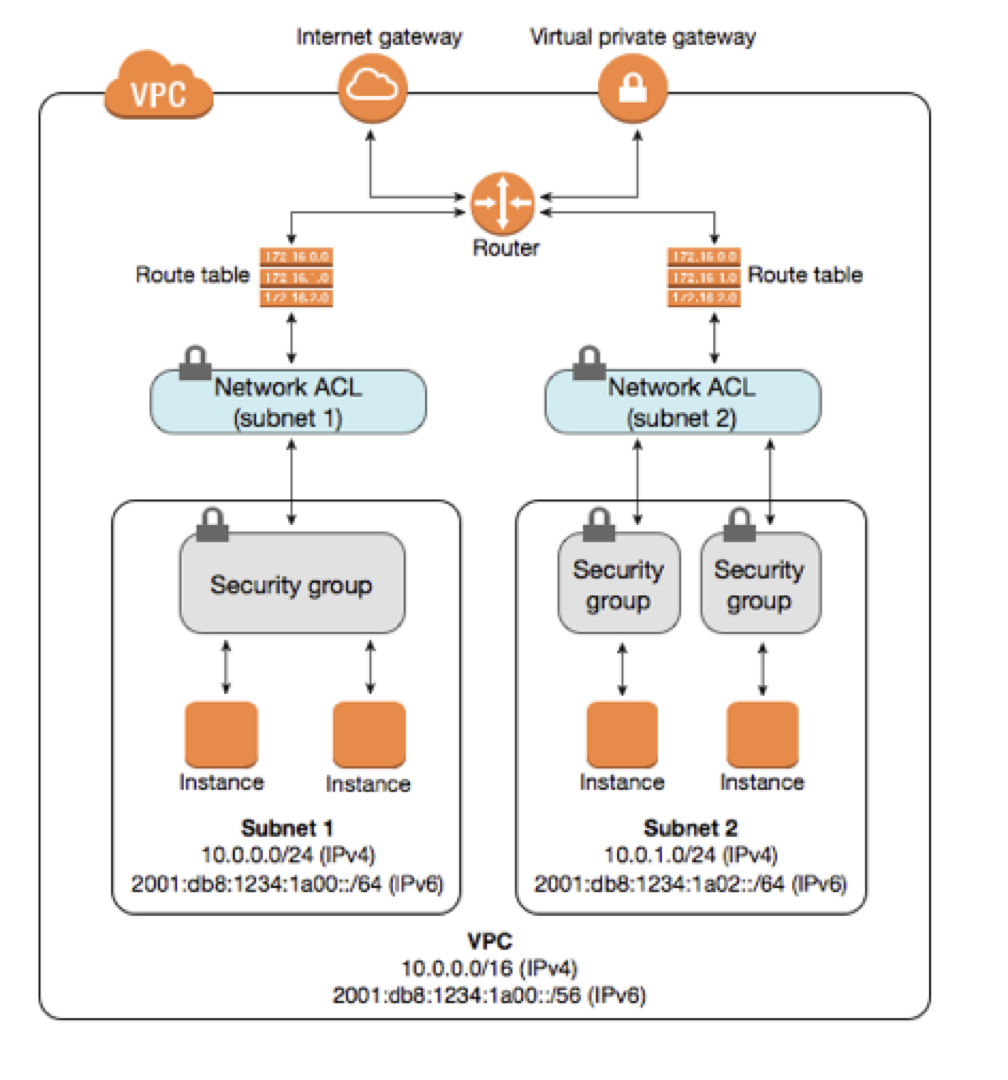

Because security groups are so powerful and useful, people often forget or don’t bother with Network ACLs. These are similar to security groups, except at the subnet level. And it’s true, if your security groups are configured perfectly you don’t necessarily need to use NACLs. But NACLs can provide that little bit of extra confidence in your environment. If you restrict access at the NACL level it doesn’t matter if someone accidentally opens up a security group more than you want it. The traffic is already stopped at the NACL level so it doesn’t go there.

Speaking of subnets, let’s highlight the distinction between public and private subnets. Public subnets have access to, and are accessible from, the internet through an Internet Gateway. Private subnets don’t have routing enabled to go through an Internet Gateway. Instead you can use a NAT Gateway to provide your instances access to the internet, but they themselves are not accessible from the internet. From a security standpoint, nothing should go into a public subnet unless it specifically needs to be accessible from the internet.

There are a couple of things that can help with this. First are the various types of Elastic Load Balancer available to us now. Don’t put your web servers directly on the internet, put an ELB in your public subnets and your instances in the private subnet. As an extra bonus, ELBs are managed by AWS which also means you don’t need to think about keeping them up to date.

You might still need to be able to access servers in these private subnets and, unless you have something like Direct Connect or a VPN connection set up, that requires a jump box or bastion server. Again though, ask yourself the question. Do these instances need to be running all the time? If they don’t, why not make them temporary instances? Especially now that AWS will be billing on a per second basis, you can write a Lambda function that spins up a new jump box with the configuration you require only when you need it.

Let’s take that idea one step further though. Why not have it so that your Lambda function will spin up the server using a key that is specific to a user? And maybe even restrict the open port to the IP they’re calling the function from? This will give you additional logging of who needed the access, and you can of course even turn it into a form where a reason has to be given for the access. And to ensure your instances don’t stay up and running forever, you can have another Lambda function set up to run at a regular schedule that destroys a jump box once it’s been running for a certain amount of time.

Secrets

Now we’ve discussed a number of ways to keep your infrastructure safe, but how about secret management? Your applications are likely to use some kinds of secrets. This can be usernames and passwords for your database, API keys for external services, or any other thing that grants your instances limited access to things.

There are many ways to deal with this, so let’s walk through a number of options where we increase our security every time. And let’s get the scariest one out of the way. Plain text passwords. This is obviously not a great way to do things, but at one point or another, we’ve likely all used it. Maybe it was temporary to ensure you can quickly continue with your work, and hopefully you remembered later on to change it. But what are some basic things you should still keep in mind here?

If you’re using CloudFormation to manage your infrastructure and pass along secrets, you should use parameters with the NoEcho flag to ensure they don’t show up. When updating your template you keep this the same by using “UsePreviousValue=true” as the value, which is the default if you do it through the Console. However, if you then pass this password to the userdata of your instance it will once again be visible. Which means that anyone with access to read the userdata will be able to see the password in plain text.

We can do better than that, so let’s improve this by encrypting the password using KMS. You can either create a key or use the default one. Make sure to use the built-in key rotation for extra security. This will still enable you to decrypt keys that were encrypted with a previous version of a key, so that is not a concern. Now that we’ve got the encrypted key, this means that just reading the userdata isn’t enough anymore. To actually learn the password, an attacker will also need to decrypt it.

However, we’re actually still passing this encrypted key through the userdata. It’s less of a risk, but it’s still a risk. So, let’s ensure we don’t need to use userdata at all to pass the secret. As mentioned for the SSH Keys and passwords earlier, we can store these secrets in a Parameter Store as well and using instance roles we can limit the instance’s access just to the specific secrets it needs. This way we only have to pass the name of the secret in the userdata and we’ve closed this loophole.

But, what if, despite all your network security, an attacker gains access to the instance itself? Depending on the application you use it for, you may still have your passwords visible there. This is true, and there is less we can do about that. But what if we don’t use any password at all? The best password is no password at all, and AWS offers the ability to use their datastores without a password by again using instance roles for this. This is the case for DynamoDB and S3, but also for MySQL on RDS and Aurora using IAM Database Authentication.

How this works for RDS and Aurora is that your instance will be able to request a temporary token for database access with a specific user database user, and then using this token to make the connection. There are some limitations to this however, especially concerning the number of simultaneous connections you can have, and obviously your application will need to support this type of authentication as well.

When it comes to secrets, there is always a risk as you need to use them somewhere, and we can’t completely remove it, but treating them as securely as possible will at least help us keep the risk down.

Conclusion

There are many other things to discuss regarding security in AWS, but we’ll leave it at this point. Let’s highlight some key points though.

- Ask questions. Always consider if access is really needed or if there is some other way to achieve the same goals.

- Build on what is there. Don’t redo the work that AWS has done for you, but focus on what makes you unique.

- Minimal access. Don’t grant access that is not needed.

- Verify. Don’t trust that just because something was safe in the past, that it is still the case.

- Automate. Not just your monitoring and alerting, but everything you can. People can forget to check something, but once it’s been automated it will be checked all the time.

To continue with your journey into AWS security, there are a couple of things that are worth reading. If you haven’t done so before, read up on the Shared Responsibility Model and then move on to the security portion of the Well-Architected Framework. These two will give you an overview of what you should focus on. Then on their Security website AWS has a list of resources relating to the security of specific services.

Additionally, the Centre for Internet Security has a 150 page whitepaper full of recommendations for securing your environment. This not only contains recommendations, but also code snippets using the AWS CLI to see if your environment follows them, thereby allowing you to easily automate this.

Lastly, AWS releases updates and features all the time, which includes their security. Keeping up to date with product announcements on their main blog will help with this, but there is also a security specific blog.