This is the third post in a series about connecting to your EC2 instances. In the first post I talked about EC2 Instance Connect and the second one was all about Systems Manager Session Manager. In this third post, I’ll have a brief comparison between the two, before looking at some ways to minimise needing this access.

Instance Connect vs Session Manager

I’m not planning to reiterate everything from the previous two posts, so I’ll jump straight to the conclusion. And hopefully, it won’t come as a surprise that I believe Session Manager is the more capable solution for connecting to your instances. While both solutions aim to do the same thing, Instance Connect focuses on improving the traditional way of connecting to your instances, whereas Session Manager tries to work around this using AWS native tooling.

Instance Connect grants more freedom to its users however, and the system for uploading temporary keys in Instance Connect is a great design. In fact, if you wish to use Session Manager as an SSH proxy, for example if you need SCP access, I highly recommend using Instance Connect as a mechanism to provide those keys. As the access is already limited by the lack of an open SSH port and the IAM controls on Session Manager, you wouldn’t necessarily run into the issue with needing to whitelist every instance either.

In the end though, the ability to completely control access through IAM, the fact that you don’t need to open ports to your instances, and that all interactions can be audited, leads me to recommend using the Session Manager whenever you need to connect to an instance. However, let’s have a look at why we need that access in the first place.

Why do we connect?

Roughly speaking, we can divide our need for access to instances in three categories :

- For development reasons

- For operations reasons

- For application reasons

Of these three, the third one is hard to avoid. For example, if a third-party application requires you to log into a Windows instance, there isn’t a lot you can do about it. In cases like that, I still recommended that you run this on its own special instance, and you ensure access is limited.

Development and operations reasons blur a bit into each other and can be quite broad. I won’t pretend that I’ll be able to cover every use case in a short blog post, let alone show an alternative that works for you, but I’ll try to highlight the three most common scenarios.

I need to see the logs!

Probably the most common reason I hear from developers (and one I’ve used often enough myself) for access to a production system is to debug something that has gone wrong. This usually means looking at application logs, system logs, or a combination of the two as they contain vital information for finding out why an application has failed. And these logs are where the application is running.

But, let’s be clear, in a modern architecture you are likely to use an auto-scaling setup where your instances might get terminated if your application has a problem. And even if you don’t let your instances scale in, you should still design for failure as accidents happen, often outside of your control.

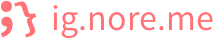

Which means that you should move your logs off of your instances. There are comprehensive third-party tools for this, but AWS also offers its own solution by using CloudWatch Logs. CloudWatch Logs works through an agent that you run on your instance and configure to send specific log files to CloudWatch. There these logs can be grouped by instance, or instance group, and log file. While you can browse log items directly from the interface, this isn’t a great experience.

Instead, you can use CloudWatch Logs Insights to query these logs or forward them to S3 so you can use Athena for even more powerful searching capabilities.

I need to do deployments!

Before we can even begin to think of debugging those logs, we first need to get our applications on those servers. In a traditional environment, this might mean updating a running application, or installing a new version alongside and switching this over. However, thinking again about a modern architecture where you design for failure and the ability to scale horizontally, you don’t want to do so by logging into each instance manually and running the commands for this.

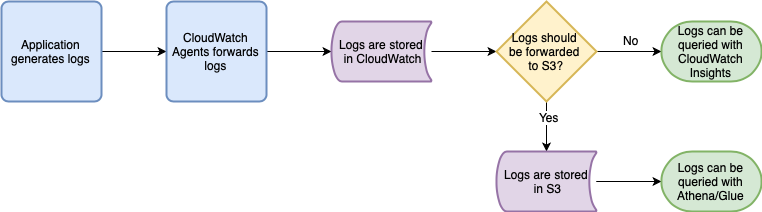

In this case, you can use CodeDeploy to update the application on your running instances. It’s even possible to configure it in such a way that, before the actual deployment happens, the application is stopped and the instance removed from the load balancer. Then after the update, CodeDeploy can do some automated checks before making it available to the load balancer again.

I need to patch security issues!

This is very similar to doing deployments. The next time a significant bug crops up that might impact the security of your instances and data, you will need to patch these holes. Again though, you don’t want to do so by manually logging into all your instances. Aside from that getting tedious, it will also make it easy to miss one or make a typo somewhere.

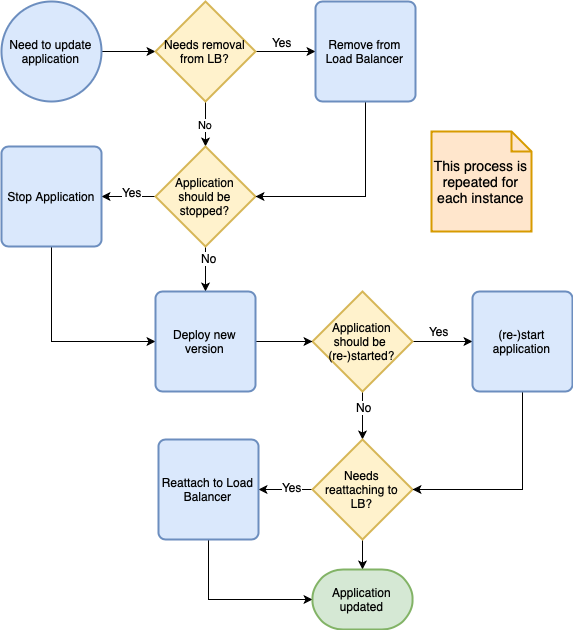

There are a couple of tools within the Systems Manager suite that can help with this. The first is Patch Manager, which allows you to automate the patching of all of your machines. For this, you will set up your instances in various “patch groups” for which you then configure baselines. This baseline determines what patches should be applied, and during the defined maintenance window will attempt to install these automatically. In general, you schedule it so your non-production servers get the updates first, and you can verify they don’t interfere with the application. As expected, there is a bit more to it than just what I mention here, and I highly recommend you read the full documentation.

Another, slightly more manual, option is to use the Run Command tool. This is similar to Session Manager in that it allows you to interact with an instance, but these are not interactive session. You send commands to a group of instances, and they do what you tell them and return the resulting output. One significant advantage here is that AWS provides a lot of Documents (which is how the commands are configured) out of the box.

Let’s go the next step

The above tools help in managing a static environment and ensuring you can do deployments and updates where necessary. In general, it’s recommended to switch to an entirely different model: immutable instances.

The concept is straightforward, although I won’t claim that the execution is always smooth. An immutable instance is one that doesn’t change after you start it. This means that after you run up an instance, you don’t patch it. Nor do you install a new version of your application on those instances. You don’t even store any data on the instance.

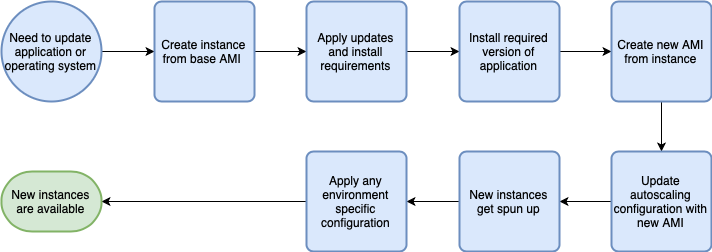

You can do this by way of installing everything before you start the instance, and then when you need to make a change, you start a new instance. Generally, the preferred way to do this is by building AMIs that have everything installed and ready to go, and then using these AMIs in an AutoScaling Group.

The advantage of this is that you can more easily test the exact setup in your development environment. Be aware that you will likely want some configuration differences between environments (for example, database credentials), and you can apply that in the user data of the instances. This also means that the process for patching your instances, updating your applications, and even a rollback to a previous version is all the same. Implied in this is that you have this process automated, but a deployment can then be as easy as updating the AMI parameter in a CloudFormation template.

Immutable instances more easily allow you to use deployments patterns such as blue/green, canary, or you can keep with rolling deployments. The exact deployment method you wish to use will likely depend on your environment and any business requirements.

Letting go

Both Instance Connect and Session Manager offer a substantial improvement over using shared keys, or enabling individual access in a self-managed way. In addition, the fact that you can use Session Manager without even needing to expose a single port makes it far more secure against attacks. Add in the fact that it offers a complete audit trail, and I highly recommend using Session Manager as your primary way to access instances.

If you need to access them, that is.

For most of my working life, I’ve been able to log into the machines my applications run on, and I can understand the loss of control when that ability is taken away. It will always feel faster to quickly log in and fix something or look at the logs on the machine itself.

Instead of thinking of it as losing control; however, I want to ask you instead to think of this as having faith in your automation. Being able to trust that what you have built will be able to weather any storm is a beautiful feeling. Yes, maybe your individual instances suffer from a particularly bad storm, but the log files that will give you clues on how to improve will be available. And if the storm goes on, you can use that automation to deploy a newer, more robust, version of your stack that can handle it.

So I ask you to consider whether you really need this feeling of control or if you can let go of your tightly managed instances. Even if you’re unsure if it will work, maybe just try it. After all, in the end, if you really, really, need it, both Instance Connect and Session Manager are there for you.