In the past I’ve had questions about how permissions work in S3, so I decided to investigate and write it up for myself so that I’ve got it all clearly described somewhere and can refer to this article.

The levels of permissions

Access to S3 buckets is managed at 3 different levels:

- Access Control Level (ACL) permissions of the bucket and objects

- A bucket policy

- IAM permissions of the user, role, or group1

All of these need to be in alignment in order to get access to an object. That means that for example a user needs to be granted access to the bucket and its objects while neither the ACL or bucket policy are blocking that user in any way.

This gives you control at each of these levels. For example, you can make individual objects public (for reading) using ACL. In the Console you do this by selecting the object and in the actions menu choose “Make public”. Similarly you can add the ACL permissions when you copy the object using the AWS CLI by adding the --acl public flag to your aws s3 cp command. That said, AWS recommends against using ACLs to manage access.

You can also make all files public using a bucket policy with the below policy. This policy overrides the individual ACLs and allows anyone access to the objects.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "PublicReadForGetBucketObjects",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:GetObject",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::yourbucket/*"

}

]

}

The third way is by granting access to a user, where you can grant specific permissions to access a bucket and/or the objects within a bucket. In the example below you can see that you can specify access to only specific directories as well.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Action": [

"s3:GetObject"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::fake.ig.nore.me/dev/*"

},

{

"Action": [

"s3:ListBucket"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::fake.ig.nore.me",

"Condition": {

"StringLike": {

"s3:prefix": ["dev/*"]

}

}

}

]

}

One other thing that can be useful when writing these IAM policies is to use variables, which allows you to use the same policy for various users2. Possibly the most useful variable for S3 buckets is ${aws:username}, but a complete list can be found in the documentation.

Access granted

When it comes to these access levels, it is important to keep in mind how they decide whether something is accessible or not. First, accessible doesn’t necessarily mean public. S3 objects can be made accessible for different users, only from certain locations, and various other factors I’ll go into in a bit.

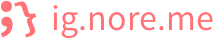

The below flowchart shows how this is decided: Access starts as denied by default. That is, if you don’t do anything special to the bucket or files you upload to S3 nobody but you3 and other users with S3 permissions in your account can access them. When it comes to permissions, you can set two kinds: allow and deny permissions. If there is a rule that denies you access, regardless of any other rules that allow access, it will be denied. So, only if you are explicitly allowed access, but not denied, will you have access.

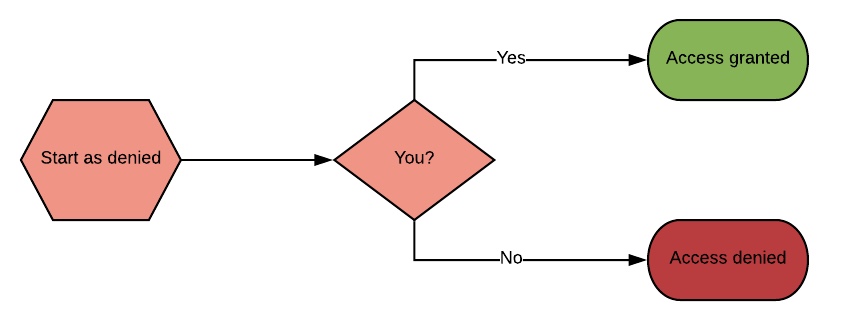

To illustrate, let’s say that you created a bucket and uploaded a file to it. As said, by default only you will have access to it4.

However, due to corporate policies you are required to then add a bucket policy as well that restricts access to only your corporate network by denying access from other IP ranges. Now, regardless of your other access permissions, you won’t be able to access that file when you’re working from home5.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Id": "S3Policy",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "IPDeny",

"Effect": "Deny",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:*",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::fake.ig.nore.me/*",

"Condition": {

"NotIpAddress": {

"aws:SourceIp": [

"123.123.123.0/24"

]

}

}

}

]

}

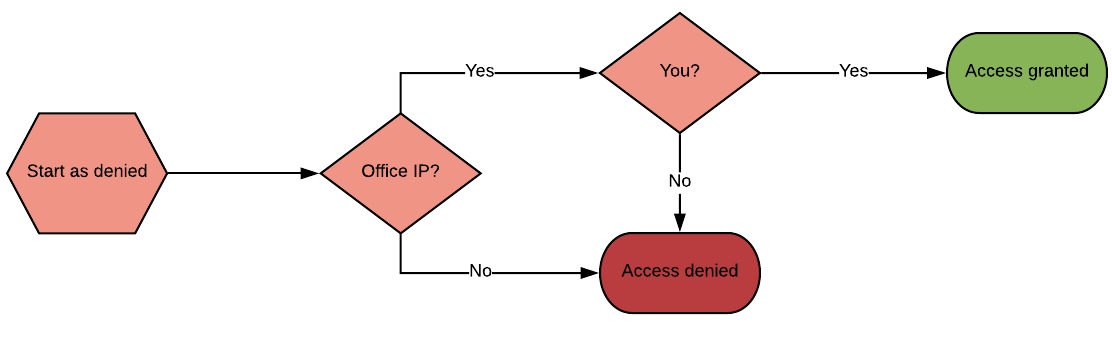

But, what would happen if the rules are changed? If instead of barring outside networks, you whitelist your corporate network? In that case, not only will you have access from outside, but anyone coming from your corporate network will have access as well. Not necessarily the setup you’re looking for.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Id": "S3Policy",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "IPAllow",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:*",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::fake.ig.nore.me/*",

"Condition": {

"IpAddress": {

"aws:SourceIp": [

"123.123.123.0/24"

]

}

}

}

]

}

Access trough a VPC Endpoint

VPC Endpoint Gateways allow you to create a direct connection from your VPC to your S3 buckets6, which doesn’t leave the AWS network. So, instead of going over the Internet as is usual for S3 calls this is a completely internal call. This is especially useful for private subnets, but it also ensures you can keep access to your buckets more tightly controlled as you can use internal calls and therefore don’t need to make anything publicly accessible.

One important distinction here is to ensure you call your s3 buckets using the s3:// prefix instead of the regular https:// as the latter will always try to use the public endpoint, regardless of a VPC Endpoint being present.

Endpoint policies allow you to limit what your endpoint has access to. Where the other policies described start from a deny point, the default policy for a VPC Endpoint is to allow access. Of course, the Endpoint policies are in addition to all the other permissions, so unless access is granted by one of these the VPC still doesn’t have access.

Bucket specific permissions

For reasons that probably won’t surprise you7, bucket specific actions can only be carried out by authenticated IAM users. This includes all of the tasks you might expect such as creating or deleting buckets. To reiterate, it is not possible to grant permission for these actions through either ACLs or bucket policies, they can only be granted at the IAM level.

User policies are the policies you assign to your IAM users, groups, and roles. If you’ve done any work with IAM you’ll likely be familiar with them already. They are the JSON files the user’s permissions are based on, whether you generated them by assigning pre-existing templates or wrote the policy yourself. IAM is a whole different subject however, so I’m not going to go into that now. Just keep in mind that by default IAM users don’t have any permissions, so if you want a user to be able to do something you’ll have to grant them that permission.

ACL vs Bucket Policy vs IAM Policy

Which leads to the last question I want to briefly highlight, when you have policies at all of these different levels which one is more important? The answer to this is: none of them. Each and every policy is equally important and is treated equally. Looking at the first flowchart, all of the applicable policies8 are applied and processed at the same time.

As mentioned at the start, using ACLs is no longer recommended and I would say that using IAM policies is probably the best way to go for managing permissions for authenticated users. If non-authenticated users need access you can then manage this using a bucket policy.

-

For readability reasons I’ll only refer to users in the rest of this article. However, all of that will count for roles and groups as well. ↩︎

-

Preferably then by applying the policy to a group. ↩︎

-

While logged in with your AWS account. ↩︎

-

Let’s also pretend there are no other IAM users in the account with S3 permissions. ↩︎

-

Barring the use of VPN, or remote desktops etc. ↩︎

-

With the introduction of VPC Endpoint Interfaces, different services require different endpoint types. Endpoint Gateways are used for S3 and DynamoDB, but please look at the documentation to see what other services are supported. ↩︎

-

aka security ↩︎

-

For non-IAM users that only means the bucket policies and ACLs. ↩︎